A reporter from Delaware called to inquire about our recent Financial State of the States report, and the “F” grade we assigned to Delaware. “Delaware has been a Triple A-rated state for 17 years – can you please explain how you can give the state an F?”

On a per-taxpayer basis, Delaware has accumulated some of the highest unfunded obligations for government employee retirement benefits in the nation. Delaware is a bit of a special case, given how high its unfunded retiree health care benefits are relative to other debt, and that unfunded position is going to be arriving on the state balance sheet in coming years. But the reporter’s question raises some broader, more fundamental issues worth discussing.

Here are seven ways Truth in Accounting’s (TIA) financial assessments differ from credit ratings:

-

Credit ratings are bond-focused. Credit ratings focus on bonds, which tend to be senior to most other obligations. In other words, bonds get “paid first.” Bondholders can have other legal means helping bondholders secure their position relative to other parties expecting payment from state and local governments. Truth in Accounting’s grades are rooted in our holistic perspective on government finance. We care about the big picture and the Average Joe (and Jane). We do not prioritize special interest groups like pensioners and bondholders.

-

State and local government bonds are issued by “sovereigns.” At a credit rating agency presentation a couple weeks ago, representatives were giving their overview of current market conditions. They began with a discussion of the fundamental strengths of municipal bonds in credit markets generally, noting they have sovereign tax authority front and center as a source of strength. Truth in Accounting doesn’t think like that. The power to tax is not necessarily a source of strength for the average taxpaying Joes and Janes.

-

Bonds can help kick the can down the road. Bonds can be a vehicle for kicking financial problems down the road. The blooming crisis facing many state and local (if not federal) governments in the United States has been driven in part by the tendency for the government and politicians to avoid short-term political pain by borrowing money, thereby buying short-term ‘success’ with long-term consequences. A “AAA” credit rating may help a state borrow money, but that isn’t necessarily a source of overall financial strength.

-

Credit ratings may follow, not lead, real financial deterioration. If we learned anything from the financial crisis of 2007-2009, it is to not take credit ratings at face value. In fact, the credit ratings industry was a central point of failure in the crisis, in part because because regulators (corrupt or otherwise) chose to make credit ratings a central element of their regulations. Academic financial studies suggest that credit ratings tend to react to, and lag, changes in market prices. This tendency also may be reflected in the next point, which is that …

-

Credit ratings may lag TIA’s Taxpayer Burden. We have compared the distribution of credit ratings across the 50 states to TIA’s Taxpayer Burden, which is our bottom-line measure of government financial position annually since 2009. They tend to run in the same direction, which isn’t surprising. States with higher credit ratings tend to have better financial positions. What is a little surprising is that, when we compare the distribution of state credit ratings from one large firm in 2009 to our Taxpayer Burdens in 2016, and then compare our Taxpayer Burdens in 2009 to their credit ratings in 2016, the Taxpayer Burdens in 2009 do a better job of anticipating the distribution of credit ratings in 2016, compared to how credit ratings in 2009 anticipated Taxpayer Burdens in 2016. Credit ratings are, in theory, forward-looking indicators, while our Taxpayer Burden is based on lagged accounting data.

-

Credit rating agencies are paid by governments. The credit rating industry has been driven by an “issuer pay” revenue model. In other words, credit rating agencies are paid by the issuers of securities—not the investors in those securities. A longer story, but this can lead to potential conflicts of interest and/or bias in favor of securities issuers, another element of the financial crisis of 2007-2009. Truth in Accounting is not paid by governments for our analysis. We are an independent, nonpartisan source of information.

-

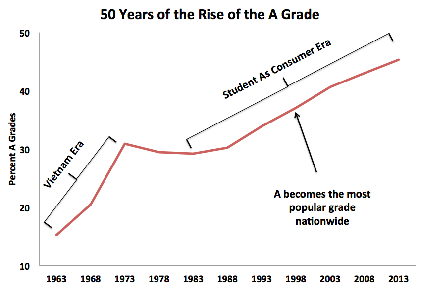

Credit rating scales themselves may reflect grade inflation / bias. In credit ratings, an “A” is a relatively bad credit. A “BBB” is borderline junk. A “B” is a junk credit. TIA’s grades range from A to F.

Back in 2006, before the financial crisis erupted and pulled the rug out from under the economy, Prem Watsa, CEO of the Canadian insurance company Fairfax Financial Holdings, offered the following prescient observations in his annual letter to shareholders:

“Finally, we continue to worry about the unprecedented issuance of collateralized bonds, mortgages and loans (we hold none!). The assumption in the marketplace is that ‘‘structure’’ will eliminate or significantly reduce all risks. So a portfolio of 100% non-investment grade bonds, sub-prime mortgages or non-investment grade corporate loans, by sophisticated structuring, can transform into securities of which 80% or more are rated A or above. This has resulted in thousands of collateralized bond issues being rated AAA while fewer than 10 corporations in the U.S. are AAA! We see an explosion coming but unfortunately cannot predict when.”

A lethal mix of government subsidies and “regulation” led to the financial crisis of 2007-2009. Hopefully, we can avoid a similar meltdown in our governments themselves.