In state and local government accounting, the income statement is called the Statement of Activities. It includes a section with expenses, offsetting fees and intergovernmental grants, and general (tax) revenue.

Among the expenses, the City of Chicago reports “Interest on Long-Term Debt.” Chicago claims to balance its budget annually, citing state law. But in the past decade, Chicago’s expenses have run billions of dollars ahead of revenue regardless, and the city’s debt (and interest) burden have mushroomed despite a period of falling interest rates generally.

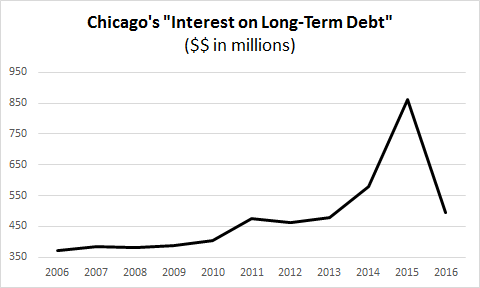

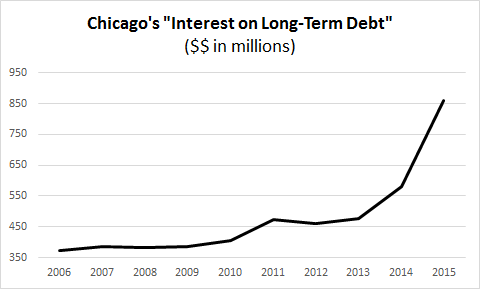

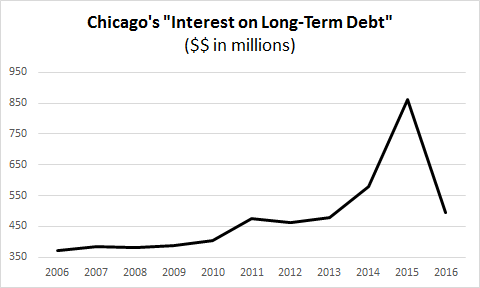

Here’s a look at what the City of Chicago reported for “Interest on Long-Term Debt” from 2006 to 2015.

In turn, here’s what happened to that line item after adding what was reported in 2016.

A recovery? A turnaround? Doesn’t look like it.

Interest on long-term debt is not the only source of interest expense. Buried in the footnotes is an annual disclosure of total city interest expense. In Chicago’s 2016 financial report, that disclosure reads:

“The total interest expense (Governmental and Business Activities) incurred by the City during the current fiscal year was $1,096.6 million, of which $49.2 million was capitalized as part of the capital assets under construction projects in proprietary funds.”

A billion dollars a year, in interest expense alone. Up from $660 million in 2006, in a period when interest rates on 10 year Treasury bonds fell from 5% to 1.5%.

But that billion dollars in 2016 was still down from a like-reported $1.5 billion in 2015.

Has Chicago been cleaning the decks? Not if the stock of outstanding debt or the projected debt service requirements are closer to the truth. From 2015 to 2016, Chicago’s total “bonds, notes, and certificates payable” remained basically flat at $10.4 billion, while the interest component of its projected debt service requirement for 2017 to 2034 rose again, from $16.3 billion to $16.7 billion.

One fly in the mud here lies in the termination of interest rate swap agreements. Chicago entered into these derivative contracts back in the mid-2000s, ostensibly to hedge against higher interest rates. But interest rates fell considerably, leading to hundreds of millions of dollars of losses on these ‘hedges.’ Chicago terminated the bulk of them last year.

Bottom line – the trends in Chicago’s projected debt service requirements for interest, the stock of outstanding bonds, notes and certificates payable, and (going forward, after the swap terminations) the footnote disclosure of interest expense are better things to watch than simply the “interest on long-term debt” reported in the income statement.