Our nation’s banking system and our central bank have radically transformed themselves in recent years, after the worst economic and financial crisis since (at least) the Great Depression. Have the changes been for the better? Are more fundamental changes on the horizon? What does this have to do with truth in government accounting?

Banks maintain ‘reserves,’ a source of liquidity to support short-term liabilities like deposits. The two main types of reserves are vault cash and, since 1913, reserve balances that banks maintain with the Federal Reserve banks.

Vault cash is an obvious ‘reserve,’ as banks hold vault cash to serve depositors that might wish to withdraw currency. And banks can tap their reserve accounts at the Federal Reserve banks as a source of currency or other funds necessary to make good on payments, either for their own account or for the account of their customers.

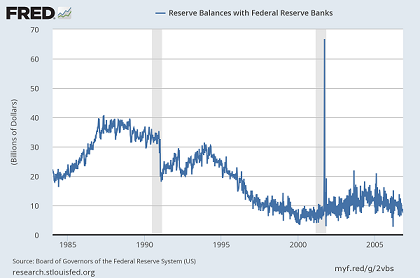

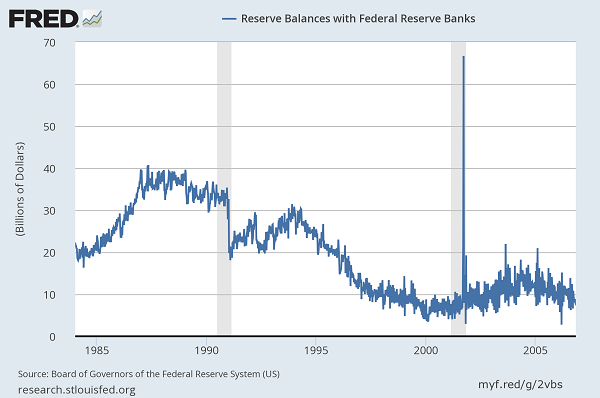

Here’s a look at bank reserve balances at Federal Reserve banks from 1985 to the end of 2006, before the onset of the massive dislocation in the crisis of 2007 to 2009:

Bank reserve balances ‘held’ at Federal Reserve Banks trended downward from the late 1980s heading into the latest financial crisis. Before the blowup, some experts discussing this trend would assert that the banking system had grown increasingly efficient in reserve management, helping to explain how reserves could decline over a period of massive growth in interbank payment volume. (that short dramatic spike in 2001 was in September).

Heading into the 2007-2009 crisis, banks maintained about $10 billion in reserve balances in the Reserve Banks.

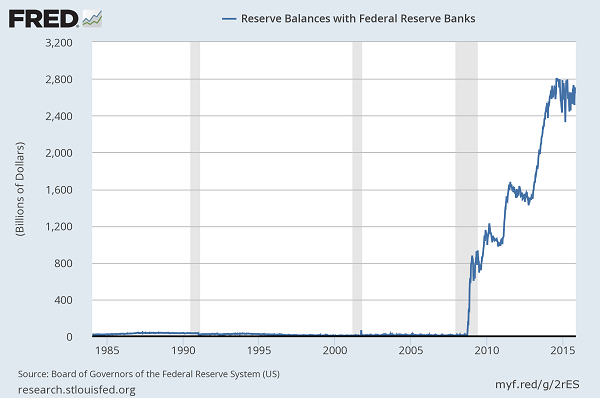

What does that picture look like today, if we update the chart and go from 1985 to 2015?

Since 2006, reserve balances have exploded, rising from a measly $10 billion to over $2.5 trillion.

The main reason? The Federal Reserve’s “quantitative easing” policy begun during the Great Depression. The Federal Reserve bought massive quantities of government and government-like securities, lifting them off the books of the banking system in return for banks getting paid in reserve balances at the Reserve Banks.

We are in a new era, in terms of the banking system and our government’s relationship with it.

A longer story, but one set of critics have questioned whether this huge increase in reserves could threaten higher future inflation, if and when banks start lending more of this liquidity in the nonbank economy.

Historically, bank reluctance to maintain higher reserves was driven by a simple fact – their price. Currency (Federal Reserve Notes) are valuable in the private sector, but demand for those notes is not as high as would have been if they paid interest. Likewise, historically, Federal Reserve balances didn’t pay banks interest.

In our new era, however, the Federal Reserve is now paying interest on reserves. The Fed has been paying a 0.25% annual rate since the end of 2008. That may not sound like a huge return or anything, but it is worth noting that it is being paid on reserve balances around $2.5 trillion, for an annual return of $6.5 billion.

A recent article by Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis consultant Christopher Phelan, titled “Should we worry about excess reserves?”, questions whether banks are threatening us with higher inflation if they convert this source of liquidity more quickly into bank loans. In turn, Phelan puts forth the idea that Federal Reserve policy could guard against this threat by selling assets significantly, or by raising reserve requirements sharply higher. The latter option, which could include a “100% reserve requirement,” would require Congress to amend current statute.

This proposal is gaining greater circulation in banking policy circles. I bring it up now because of a related “truth in accounting” issue.

As the 2007-2009 crisis began to flower, another source of banking system liquidity began to mushroom. Our banks move over a trillion dollars a day among themselves over a funds transfer system at the Federal Reserve called “Fedwire.” The Federal Reserve guarantees payments to a receiving bank on this system, even if the sending bank didn’t have the reserves on its account at the Fed during the day at the time it sent the payment. This leads to something called a “daylight overdraft,” and a source of risk to the Reserve Banks.

During the 2007-2009 crisis, daylight overdrafts began rising dramatically, reaching about $275 billion at peak levels. With the massive quantitative easing program, however, and the huge increase in bank reserves, the need for overdraft liquidity fell sharply.

Does this mean the risk to the Reserve Banks went away?

No, not necessarily. It morphed over to the Reserve Bank balance sheets, whose huge expansion led to the explosion in bank reserve balances.

Those huge Reserve Bank balance sheets are not riskless. A significant increase in long-term interest rates and/or reduced credit quality on Reserve Bank securities portfolios are a risk to the United States Treasury.

Again, a longer story, but all this relates to a very curious late-1990s set of testimony from members of the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors to Congress that access to Fedwire constituted a significant source of subsidy to banks. One reason this testimony was curious is that every year, the Federal Reserve produces accounting statements ‘showing’ that the Reserve Banks fully recover all direct and indirect costs of providing its payment services, as required by the Monetary Control Act.

The risk in the balance sheets in the Reserve Banks can be viewed as an indirect cost of shielding the Reserve Banks from losses during the 2007-2009 financial crisis, via quantitative easing.