The Chicago Sun-Times reported today on the release of CPS’ annual financial report. The headline was “CPS finishes year with surplus as CTU talks get going.”

Sun-Times education reporter Mitchell Armentrout wrote that CPS administrators “offered some rare positive news,” as the year ended with $324 million “left over in CPS’s general operating fund.” Armentrout included favorable impressions offered by the CPS controller, the Chicago Teachers Union president, and the president of the Chicago Board of Education. Armentrout did not cite any independent outsiders in his article.

The article and its official sources paint a picture of improving finances, based on the surplus reported for the CPS general operating fund at fiscal year-end (June 30, not December 31, 2018).

A “surplus” sounds like they have more than they need, right?

Unfortunately, government officials long have anchored their communications to the public using unreliable and deceptive cash-based accounting results. Longer story short, one way to improve your “cash” position (and general operating fund balance), in the short-run, anyway, is to run up your credit card.

Where have CPS’ finances been heading, based on more reliable accrual-based accounting?

Those results are to be found not in the statements for the general operating fund, but earlier, in the two main (and first-presented) financial statements, which go unmentioned in Armentrout’s article. They are the Statement of Net Position and Statement of Activities, which can be found on pages 44-46 in the CPS annual report here.

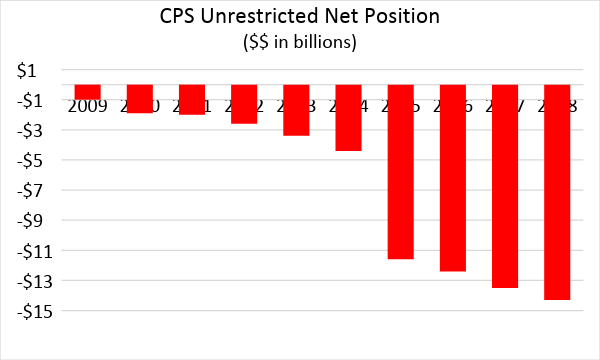

The Statement of Net Position takes a balance sheet, point-in-time perspective. It’s basically a “what you have, minus what you owe, is what is left over” framework, showing assets, liabilities, and net position (assets minus liabilities). Some assets are restricted for specific uses, however, and a better bottom-line measure to watch is the “unrestricted net position” (similar to shareholder equity in the private sector).

Here’s what that looks like for CPS over the last decade, through 2018.

Did CPS finances improve last year? Does it look like it ended with a ‘surplus?’

That massive drop in 2015 arrived because these statements, which are better to watch than the funds statements used and abused by political messaging, aren’t always based on reliable accounting standards, either. In 2015, CPS (and other state and local government entities) finally recognized pension liabilities as debt on their balance sheet, making what was ‘left over’ (which was already negative) look even worse. The important point for now, however, is that this unrestricted net position has consistently deteriorated in recent years.

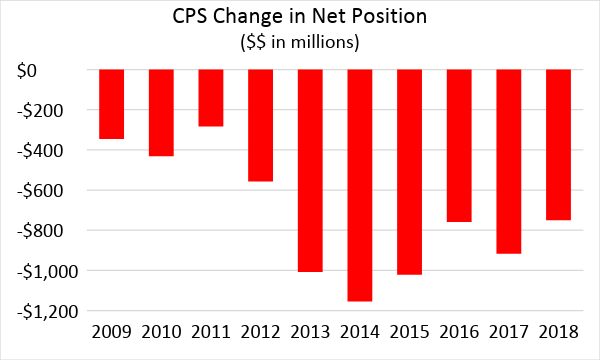

The Statement of Activities is the next statement presented. It is based on income statement framework, covering a period of time, not a point in time. It also produces a "what is left over" result, however. After adding up revenues, it subtracts expenses, leading to a bottom-line called "Change in Net Position" (like net income, for private sector companies). Here’s a look at the annual change in net position reported for CPS in the last decade.

CPS lost money every year from 2009 to 2018, with red ink totaling more than $7 billion over that time frame. Things improved in 2018, but only in a very narrow sense—CPS lost less money than it did the year before. But an $800 million shortfall is not good news.

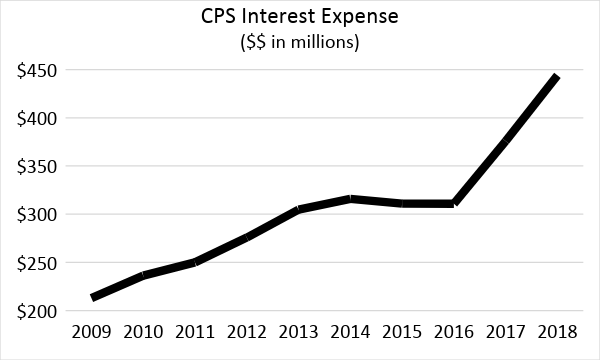

One way to cut through the complexity underlying these statements is to focus on interest expense—the cost of borrowing money. CPS has filled the massive gap in expenses over revenue by borrowing lots and lots of money—from its workers, in the form of unfunded retirement promises, and from anyone willing to buy lots and lots of bonds.

General market interest rates have fallen significantly since 2009. Other things equal, that should lead to a lower interest burden for CPS, right? Here’s interest expense reported on the Statement of Activities for CPS since 2009:

Interest expense rose steadily from about $200 million in 2009 to $300 million in 2016, and then spiked higher in 2017 to 2018.

Is this a picture of improving financial conditions?

Chicago Board of Education President Frank Clark wrote a letter introducing the report, in which he cited the recent development of a “more equitable funding formula adopted by the state,” which “has allowed CPS to achieve improved financial stability.” That financial stability has yet to appear in CPS’ overall financial results, however -- the same results he stated the Board was pleased to present. He also stated:

“The more equitable funding formula adopted by the state has resulted in hundreds of millions of dollars in additional resources for students with the potential for additional resources that would bring CPS closer to funding equity if fully funded.”

The potential for additional resources aren’t resources—they are potential resources. And the “if” preceding the “fully funded” at the end of the sentence above may be a big if.

Nonetheless, Clark goes on to say “These additional funds are supporting our vision for the future of Chicago Public Schools”—as if these funds exist today, in the present tense.

Citizens and taxpayers have to do their own homework. They can’t take communications by government officials—and reporting in mainstream media—at face value.