The City of Chicago has accumulated massive debts, even as it has long told its citizens that it balances the budget every year as required by state law. It has sold billions of dollars of long-term bonds and distributed billions of dollars of unfunded promises for retirement benefits for its employees. It has borrowed lots of short-term money too, from suppliers as well as banks and other lenders.

Money isn’t free. It costs money to get money. That’s called interest. So how much interest expense is Chicago incurring every year? How much does that compare to a neighboring city, for example, Indianapolis?

This isn’t such a simple question as one might hope, for such an important question.

Let’s take a peek at Chicago’s income statement (see p. 34). For state and local governments, that’s called the “Statement of Activities.” Chicago’s income statement has included an expense line item titled “Interest on Long-term Debt.” In 2020, that amount was reported to be $620.3 million, or about $230 for every man, woman and child in the city.

The income statement (p.28) for the City of Indianapolis reported $50.3 million for a similar line item in 2020. On a per-capita basis, that amounted to $57, or about one-fourth of the load for Chicagoans.

There’s at least one distinction worth noting, however, in comparing these line items between Chicago and Indianapolis. The line item for Indianapolis is titled simply “Interest,” not “Interest on Long-term Debt.”

You can compare Chicago to Indianapolis on another dimension relating to their respective interest burdens. That comes from a different financial statement, an underlying “funds” statement called the “Statement of Revenues, Expenditures, and Changes in Fund Balances.” Governments provide these statements for both “Governmental” and “Proprietary” funds. In 2020, Chicago reported $593.6 million in “Interest and other Fiscal Charges” for its governmental funds, and $554.7 million in “Interest Expense” for its proprietary funds. Indianapolis reported $76.9 million for this item (“Interest on Bonds and Notes”) in its governmental funds in 2020, and no interest expense for its proprietary funds.

Adding up governmental and proprietary funds, then, Chicago reported $1.1 billion in total interest expenditures in its funds statements in 2020, about 15 times as much interest (on this basis) as Indianapolis.

Stepping back from this tedious math for a minute, consider a simple fact. Last year, the City of Chicago had more than $1 billion in INTEREST EXPENSE ALONE.

In contrast to the $620.3 million in “Interest on Long-Term Debt” that Chicago reported on the overall Statement of Activities in 2020, Chicago included a footnote disclosure that identifies the “total interest expense incurred by the city.” In 2020, that came to $1.3 billion.

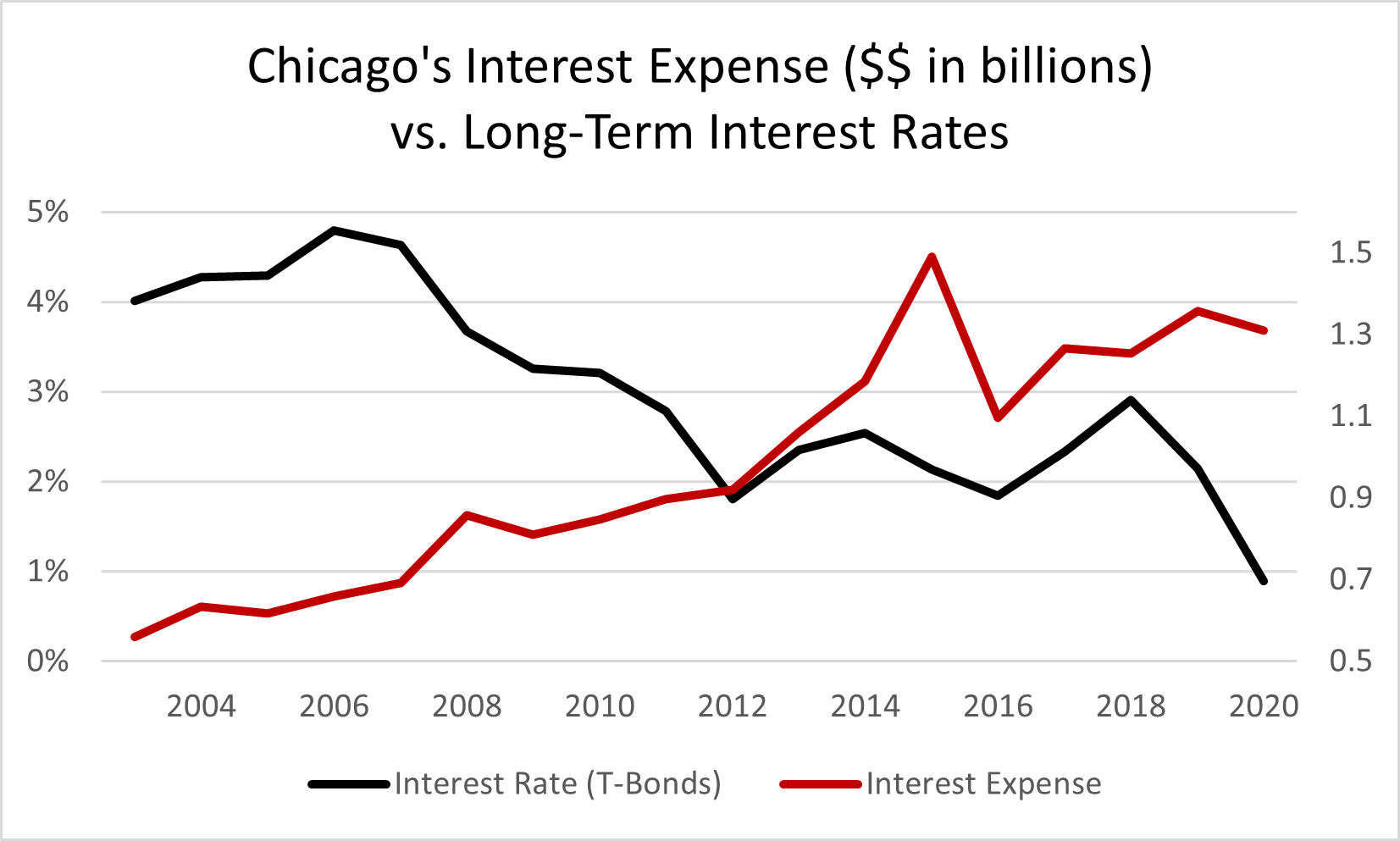

The chart below compares this annual amount included in the footnotes to long-term interest rates in the United States since 2003, the first year that Chicago currently has for its historical annual financial reports on its website.

From 2003 to 2020, long-term interest rates fell 80 percent, to less than one percent, yet during the same period the City of Chicago’s interest expense more than doubled, climbing above $1 billion a year. And from 2003 to 2020, Chicago’s total interest expense rose ten times faster than it did in Indianapolis.

So much for “balancing the budget” every year.

Meanwhile, after the onset of the pandemic last year, Chicago’s debt load has increasingly become a load not only for Chicagoans. Massive federal government “relief,” “rescue,” and “stimulus” dollars have arrived, indirectly sharing Chicago’s burden with the rest of America.

That $1.3 billion in interest expense may be a load for Chicagoans and other taxpayers, but it is the opposite of a load for some other people. Those are the people getting paid the interest. Who are they, and what influence do they have on Chicago (and U.S.) financial policies?