A question like this is normally a no-brainer. You look at total assets, report what they say, and move on.

In government accounting, however, “normal” can get pretty strange. Especially in Illinois.

Here’s a link to Illinois’ latest Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR). You can see the balance sheet (the “Statement of Net Position”) on page 32.

It’s worth noting the date on the latest balance sheet. It is June 30, 2017.

So we really don’t know how big Illinois’ balance sheet is right now. The latest date for which we have audited financial statements with a balance sheet was 616 days ago.

The Illinois CAFR is prepared in the office of the Illinois Comptroller. In November 2018, Susana Mendoza won the election for the Illinois Comptroller. Eight days later, she announced she would be running for Mayor of Chicago. She lost in that election, in late February 2019.

The Comptroller has clearly been busy in recent months, but maybe the financial reporting process wasn’t as high on the agenda as normal, or at least on her agenda. Last year, Illinois’ CAFR was dated March 15. It will be interesting to see how long it takes the Comptroller’s office to deliver the report this year.

So how about that 616-day-old balance sheet? The first page includes the reported assets, for both the primary government and the component units. Within primary government, amounts are reported for Governmental Activities and Business-Type Activities, leading to total assets of $54.3 billion for the primary government.

Component units are also important in government financials. They are legally separate organizations for which the primary government is financially accountable, such as state universities. Adding the assets of Illinois’ component units to those of the primary government gets you another $27.8 billion, for total assets of $82.1 billion.

Normally, balance sheets include assets, liabilities, and net position. Assets minus liabilities leaves you with a net position. But take a closer look at the Illinois balance sheet, at the stuff right below the assets.

That’s when things get really strange. That’s the section titled “Deferred Outflows of Resources.”

What does “Deferred Outflows of Resources” sound like to you? Are they a good thing, or a bad thing?

These puppies first arrived in state and local government balance sheets in 2010. Back in the mid-2000s, some state and local governments, concerned about the risks of refinancing debt down the road if interest rates were to increase, began to enter into interest rate swaps -- derivative transactions -- with financial institutions. These swap deals would have paid governments if interest rates rose, offsetting the costs of refinancing at higher rates.

Trouble is, interest rates began to fall over coming years, leading in some cases (like the City of Chicago and the State of Illinois) to massive liabilities for losses on these transactions.

These liabilities weren’t on the balance sheet until 2010, when they were finally recognized. It took the Governmental Accounting Standards Board about a decade longer than the Federal Accounting Standards Board to require recognition of over-the-counter derivative positions in the financial statements.

In accounting, there are debits and credits. When you recognize a liability, you credit the account. But in the dual-entry system, every credit has a related debit, and vice versa.

In Accounting 101, they taught us that when you recognize a liability you previously didn’t acknowledge, the offsetting debit is a loss, one that hits the income statement and, in turn, the net position.

But that’s not what GASB did on those swaps losses.

Instead, the new “Deferred Outflows of Resources” concept was born. The offsetting debit (in Chicago and Illinois) for hundreds of millions of dollars of liability arrived in that section of the balance sheet.

These deferred outflows are added to the assets in calculating the net position! Therefore, they insulate the reported net position from taking a hit from the hundreds of millions of dollars in new liabilities recognized on the swaps.

If governments hadn’t entered into these swap arrangements, they would have been better off, so this appears like an overly creative way to avoid reporting a loss. There may be a good reason for this accounting treatment, but I haven’t seen it explained well yet.

How about the latest Illinois balance sheet? How big are those deferred outflows of resources? What exactly is in that stuff?

Keep looking down the balance sheet on page 32. Below total assets lies the “deferred outflows of resources” section. Looking at the primary government total, what do you see?

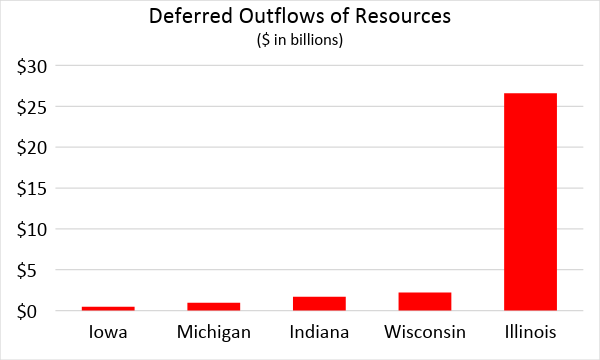

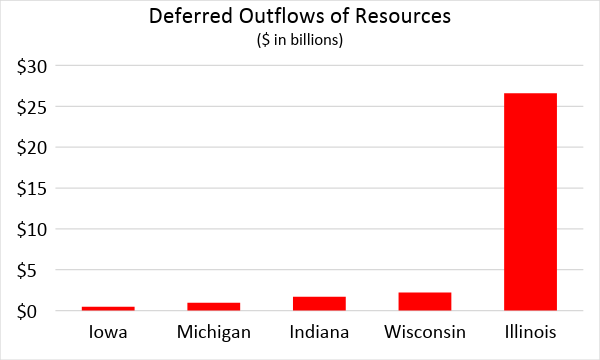

In addition to the $54.3 billion in total assets in the upper section, there is another $26.6 billion in deferred outflows! They are more than half of total assets!

And the biggest line item in there? “Deferred outflows of resources – pensions.”

That $26.6 billion is added to the $54.3 billion in assets, before subtracting liabilities (and deferred inflows), to get to the net position.

So it sounds like that $26.6 billion must be a good thing, right?

Let’s look at the balance sheet for the previous year. It is also on page 32. That year, there were only $12.2 billion of these “good things.” Deferred outflows of resources then doubled in 2017.

What happened? Why did the deferred outflows double? That must be a good thing, if they are added to the assets, right?

From 2016 to 2017, Illinois’ reported net pension liability went from $116.0 billion to $137.7 billion. That’s not a good thing, right? Why did it go up so much?

And speaking of what do we know and when do we know it, note that state and local governments are allowed to choose the current year or the prior fiscal year, when reporting the pension valuations and related liabilities. The Illinois June 30, 2017 balance sheet relies on a June 30, 2016 pension valuation.

One reason Illinois’ reported net pension liability went up so much in fiscal 2017 (based on the fiscal 2016 valuation) is that the pension plans changed the assumptions on which they rely for estimating the pension liability. This means they either realized or confessed that they had been low-balling the liability.

When they fessed up, the liability got bigger. And the “deferred outflows of resources” got bigger too, effectively insulating the net position from a big hit that otherwise would have arrived given the larger pension liability. The impact of those changes in assumptions are then smoothed in, over time, for the income statement and balance sheet.

What do you think? Should governments be allowed to smooth their reported results like this?

Here’s a look at the total deferred outflows of resources reported by Illinois and neighboring states in fiscal 2017.

So, what do you think? Is the Illinois balance sheet as big as total assets, or as big as total assets plus deferred outflows of resources?

Having fun yet? Welcome to world of securing government financial accountability.