A balance sheet can be referred to as a “snapshot.” In theory, it provides a window into the financial health of an organization at a point in time, as opposed to the income statement, which reports on performance over a period of time.

There are some important qualifiers, however, in the “point in time” assumption for what a balance sheet provides. Many assets are carried on the books based on their historical cost, for example.

In government-land, a really interesting if not troubling qualifier arises for the ‘point in time’ assumption for the balance sheet. For their pension liabilities, many state and local governments choose not to include the latest available actuarial valuations for their pension liabilities. This can lead to some really strange (and troubling) issues.

Back in December, the State of Minnesota (brr!) issued its annual financial report for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2016. Like many other states, Minnesota’s “Statement of Net Position” (the balance sheet) included a net pension liability calculated with an actuarial valuation from June 30, 2015, not June 30, 2016. The auditor’s letter on the financial statements included the following cautionary note:

“As mentioned in Note 8 to the financial statements (on page 113), most defined benefit plans changed a key assumption used to calculate the net pension liability the State of Minnesota will report in fiscal year 2017; the plans changed the long-term projected rate of investment return from 7.9 percent to 7.5 percent. That change, along with changes to other actuarial assumptions, will significantly increase the net pension liability the State of Minnesota will report for fiscal year 2017.3 For example, the state’s reported net pension liability for its share of the State Employees Retirement Fund will increase from about $1.1 billion at June 30, 2016, to about $9 billion at June 30, 2017, an increase of over 700 percent.”

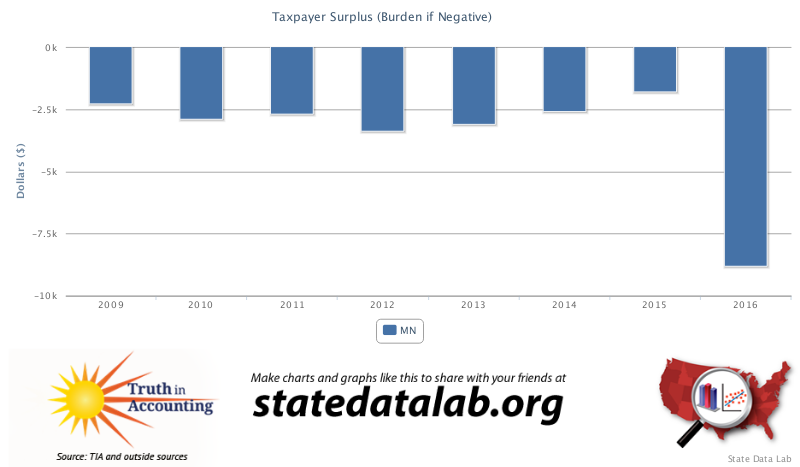

Truth in Accounting uses the financial statements reported by state and local governments in calculating our “Taxpayer Burden.” But we choose to use the latest actuarial valuation report, not the older reports used by the governments, in our appraisal. This helps explain why our “Taxpayer Burden” posted a dramatic decline in Minnesota last year.

Why might this send the City of Big Shoulders into a Deep Freeze?

In her letter introducing the latest annual report for the Minnesota State Retirement System, Chair Mary Benner explained that “changes in various actuarial assumptions including expectations for member and retirees living longer had a significant effect on the retirement plans’ funding status.” The system updated its mortality assumptions, switching from the RP-2000 table to the newer RP-2014 table. In turn, the implied increase in benefit liability led the system to use a lower “blended” discount rate, as required under new accounting standards, triggering the large/massive increase in the reported pension liability.

Which mortality table do you think Chicago pension plans are using? The latest RP-2014? Nope. All but one of the Chicago plans use the RP-2000 base mortality table. For example, the massively-underfunded Chicago teachers’ plan used the RP-2000 in its latest valuation. And in its latest valuation, the plan did not use a discount rate blended for periods after plan assets are exhausted, given that it did not project the plan to run out of assets for at least the next 107 years.

It may have to, if and when it updates from the RP-2000 table.

Brr!